Getting to know Android (Part 1)

The consumer mobile application market has grown in the last couple of years with the introduction of Android, iPhone and iPad platforms among others. These applications have provided convenient access to bank accounts, credit card data, personally identifiable information, travel itineraries and personal emails. The enterprise mobile applications extend corporate networks beyond the perimeter devices and thus potentially expose these organizations to new types of security threats.

Security risks associated with these applications can often be identified and mitigated by subjecting them to secure testing. Compared to web applications, mobile applications are harder to test for security, and hence they are less tested. At the same time, these applications are not necessarily more secure than web applications.

So in order to understand how this mobile world works and how to test mobile applications for security, this is the first blog post where we are going to talk about some topics as:

- Android Architecture

- Mobile Security Layers

- OWASP Mobile Guidelines

- Analysis Tools

- Creation of a test environment

- Methodologies

1. Android Architecture

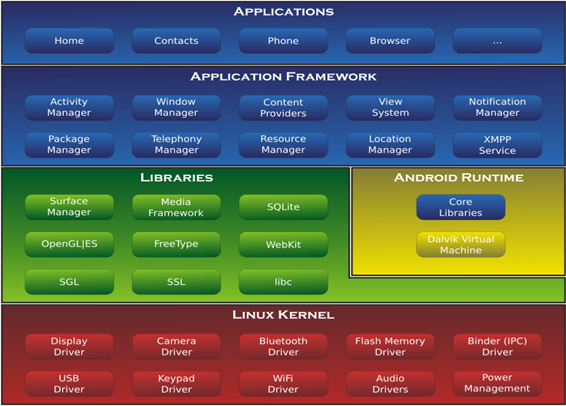

The following diagram shows the major components of the Android Architecture. The Android Operating System can be referred to as a software stack of different layers, where each layer is made of several program components. Together it includes operating system, middleware and important applications and each layer provides different services to the layer just above it. Each layer will be described in more detail below for a better understanding.

1.1- Linux Kernel

The first layer that we are going to talk is the Linux Kernel which is the basic layer. The whole Android Operating System is built on top of the Linux 2.6 Kernel with some architectural changes made by Google. This Linux is the one who interacts with the hardware and contains all the essential hardware drivers. These drivers are programs that control and communicate with the hardware. The Linux Kernel also acts as an abstraction layer between the hardware and other software layers. Android uses the Linux also for all its core functionality such as memory management, process management, network stack, security settings and driver model.

1.2- Libraries

The next layer is the Android’s native libraries. The Android includes a set of C/C++ libraries used by the various components of the Android system in order to enable the device to handle different types of data and each one is specific for a particular hardware. Bellow we list some of the core libraries:

- System C library: a BSD-derived implementation of the standard C system library (libc), tuned for embedded Linux-based devices;

- WebKit: It is the browser engine used to display HTML content.

- SQLite: A powerful and lightweight relational database engine available to all applications.

- FreeType: Bitmap and vector font rendering.

- Media Framework: The media framework provides different media libraries which are based on PacketVideo’s OpenCORE. These libraries support playback and recording of many popular audio and video formats, as well as static images files, including MPEG4, H.264, MP3, AAC, AMR, JPG, and PNG.

- SGL: The underlying 2D graphics engine.

- OpenGL: An implementation based on OpenGL ES 1.0 APIs. The libraries use either hardware 3D acceleration (where available) or the included, highly optimized 3D software rasterizer. It also can render 2D. ** Surface Manager: Manages access to the display subsystem and seamlessly composites 2D and 3D graphic layers from multiple applications.

1.3- Android Runtime

The Android Runtime consists in Core Java libraries and of Dalvik Virtual Machine.

- Core Libraries

- These libraries are different from Java SE and Java ME libraries. However these libraries provide most of the functionalities defined in the Java SE libraries.

- Dalvik Virtual Machine

- The Dalvik Virtual Machine is a type of Java Virtual Machine used by android devices to run applications. Each application runs in its own process, with its own instance of the DVM which is optimized for low processing power and low memory environments. Unlike the JVM, the Dalvik Virtual Machine (register-based) doesn’t run .class files instead it executes files in the Dalvik Executable (.dex) that are built from .class files at the time of compilation (by the included “dx” tool) which are optimized for minimal footprint and to have a higher efficiency in low resource environments.

- Dalvik has been written so that a device can run multiple Virtual Machines simultaneously and efficiently providing security, isolation, memory management and threading support, which the Dalvik VM relies on the Linux Kernel for their functionality. It is developed by Dan Bornstein from Google.

1.4- Application Framework

These are the blocks that our applications directly interact with. By providing an open development platform, Android offers developers the ability to build extremely rich and innovative applications. Developers are free to take advantage of the device hardware, access location information, run background services, set alarms, add notifications to the status bar, and much, much more.

Developers have full access to the same framework APIs used by the core applications. The application architecture is designed to simplify the reuse of components. Any application can publish its capabilities and any other application may then make use of those capabilities (subject to security constrains enforced by the framework). This same mechanism allows components to be replaced by the user.

Underlying all applications is a set of services and systems, including:

- A rich and extensible set of “Views” that can be used to build an application, including lists, text boxes, buttons, and even an embeddable web browser.

- “Content Providers” that enable applications to access data from other applications (such as Contacts), or to share their own data.

- “Resource Manager” providing access to non-code resources such as localized strings, graphics, and layout files.

- “Notification Manager” that enables all applications to display custom alerts in the status bar.

- “Activity Manager” that manages the lifecycle of applications and provides a common navigation backstack.

- “Telephony Manager” that manages all voice calls. We use telephony manager if we want to access voice calls in our application.

- “Location Manager” using GPS or Cell Tower.

1.5- Applications

Applications are the top layer in the Android architecture and this is where our applications are going to fit. Several standard applications come pre-installed with every device, such as:

- SMS client app

- Dialer

- Web browser

- Contact manager

- Email client

- Calendar

- Maps

- Contacts

- Etc…

The developers are able to write an application (written using Java programming language) which can replace an existing system application. That is, they are not limited in accessing any particular feature. You are practically limitless and can do whatever you want to do with the android (as long as the users of the application permit it). Thus Android is opening endless opportunities to the developer, but at the same time can create serious issues from the security point of view, and that is what we are going to talk more ahead.

2. Mobile Security Layers

The rapid growth in smartphone adoption also produced rapid changes in application world where they’ve been changing and moving to mobiles and with these changes private and sensitive information is being pushed to the new device perimeter at an alarming rate. The smartphone mobile device is quickly becoming ubiquitous. While there is much overlap with common operating system models, the mobile device code security model has some distinct points of differentiation.

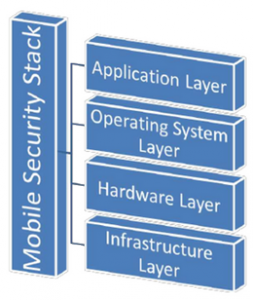

The mobile code security stack can be broken up into four distinct layers. The lowest layer of the stack is the infrastructure layer, followed upward by the hardware, operating system and application layers. These security stack layers each define a separate section of the security model of a smartphone or mobile device.

Each layer of the Mobile Code Security model is responsible for the security of its defined components. The upper layers of the stack rely on all lower layers to ensure that their components are appropriately safe. This abstraction based model allows the design of a particular mobile security mechanism to focus on a single specific area of concern without expending the resources required to analyze all layers that support its current location within the stack.

2.1– Infrastructure Layer

This layer is the foundation that supports all of the other tiers of the model. The majority of the functional components at this layer are owned and operated by a mobile carrier or infrastructure provider, however integration into the handset occurs as data is transmitted from this tier upward. Cellular voice and data carriers operate the infrastructure that carries all data and voice communications from end point to end point. The security components at this level typically encompass the protocols in use by the carriers and infrastructure providers themselves. Examples of such protocols include code division multiple access protocol (CDMA), global system for mobile communications (GSM), global positions system (GPS), short messaging systems (SMS), and multimedia messaging systems (MMS). Due to the low foundational nature of this security tier, flaws or vulnerabilities discovered at this tier are generally effective across multiple platforms, multiple carriers, and multiple handset set providers.

2.2– Hardware Layer

As we move to the second tier of the mobile code security stack, we are moving into the realm of a physical unit that is typically under direct control of an end user. The hardware layer is identified by the individual end user premise equipment, generally in the form of a smartphone or tablet style mobile device. The hardware layer is accessible to the operating system allowing for direct control of the physical components. This hardware is generally called the “firmware” and is upgraded by the physical manufacturer of the handset. Security flaws or vulnerabilities discovered at this layer typically affect all end users who use a particular piece of hardware or individual hardware component. If a hardware flaw is discovered in a single manufacturer’s device, it is more than likely that all hardware revisions using that similar design and/or chip will be effected as well.

2.3– Operating System Layer

This layer corresponds to the software running on a device that allows communications between the hardware and the application tiers. The operating system is periodically updated with feature enhancements, patches, and security fixes which may or may not coincide with the patches made to the firmware by the physical handset manufacturer. The operating system provides access to its resources via the publishing of application programming interfaces. These resources are available to be consumed by the application layer as it is the only layer higher in the stack than the operating system itself. Simultaneously, the operating system communicates with the hardware/firmware to run processes and pass data to and from the device

Operating Systems flaws are a very common flaw type and currently tend to be the target of choice for attackers that wish to have a high impact. If an operating flaw is discovered, the entire install base of that particular operating system revision will likely be vulnerable. It is at this layer, and above, where software is the overriding enforcement mechanism for security. Specifically due to the fact that software is relied upon, the operating system, and the application layer above, is the most common location where security flaws are discovered.

2.4– Application Layer

The application tier resides at the top of the mobile security stack and is the layer that the end user directly interfaces with. The application layer is identified by running processes that utilize application programming interfaces provided by the operating system layer as an entry point into the rest of the stack.

Application layer security flaws generally result from coding flaws in applications that are either shipped with or installed onto a mobile device after deployment. These flaws come in classes that are similar to the personal computing area. Buffer overflows, insecure storage of sensitive data, improper cryptographic algorithms, hardcoded passwords, and backdoored applications are only a sample set of application layer flaw classes. The result of exploitation of application layer security flaws can range from elevated operating system privilege to exfiltration of sensitive data.

On part two we will look at setting up a security testing environment for android apps and look at how to analyze them.

References:

- http://developer.android.com/about/index.html

- http://www.veracode.com/security/mobile-code-security